The last Labor government was ultimately destroyed by its determination to defend the interests of big business and manage capitalism, writes Mark Gillespie

After nine years of Coalition government, Scott Morrison has finally been driven from power.

Compared to the last time Labor won office, expectations are far lower, with Anthony Albanese sticking to a small target strategy limiting what Labor has promised. But the last Labor government still holds important lessons on what we can expect from Labor in power.

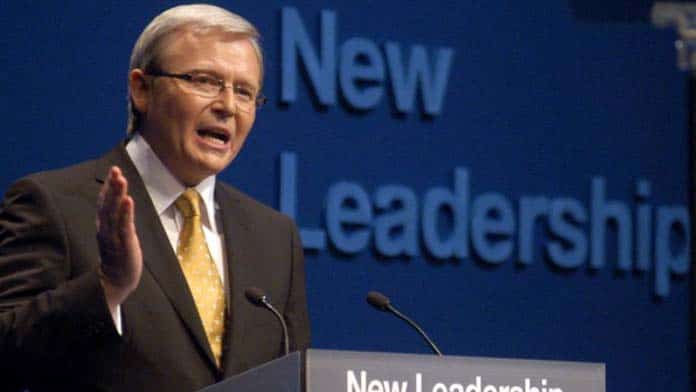

In 2007 Kevin Rudd won office on a massive 5.44 per cent swing, picking up 23 new seats—even unseating Prime Minister John Howard in Bennelong. After 11 and a half years of Coalition rule there was a deep mood for change.

On the back of Rudd’s ratification of the Kyoto Protocol and apology to the Stolen Generations in his first months in office, his approval rating soared to 70 per cent. The Liberals were in complete disarray and in opposition in every state and territory.

But it all ended in tears. After the 2010 election Labor—then led by Julia Gillard—only just managed to hang onto power by forming a minority government with The Greens and independents. Then in 2013—with Kevin Rudd now back in the leadership—Labor was crushed by Tony Abbott, achieving their lowest primary vote since the 1930s.

How could Labor squander all this support? Labor’s problems stemmed from their commitment to managing capitalism. When capitalism is booming moderate reforms for workers can be delivered while corporations keep their profits up, but in times of stagnating growth, managing capitalism “responsibly” means attacking workers.

Rudd and Gillard continually delivered policies tailored to the needs of big business. When the Global Financial Crisis struck in 2008, Rudd stimulated the economy and took the budget into deficit as he talked about “saving capitalism from itself”. Mostly, Rudd was concerned to save capitalism. The Treasurer, Wayne Swan, as early as 2010 was back to promising Labor would deliver budget surpluses.

Instead of redistributing wealth to raise workers’ living standards they focused on restoring profits. And pursuing budget surpluses meant making cuts to services including welfare spending and education.

Rudd and Gillard could not deliver genuine reform and the longer they were in office the more the gap between their rhetoric and the reality was exposed. Inevitably, this meant disillusioning Labor’s own working class supporters.

Not just an echo

When Kevin Rudd replaced Kim Beazley as leader in 2007 he seemed like a breath of fresh air. Beazley had been a minister in the Hawke and Keating Labor governments and was very much associated with their pro-market economic reforms.

Rudd promised to be an “alternative, not just an echo”. He talked about “fresh ideas”, a “technological revolution”, an “education revolution” and “an economy for the 21st century” while criticising Howard’s “free market fundamentalism”.

Rudd gave expression to the many grievances with Howard. He described climate change as “the moral question for our time” and promised to ratify the Kyoto protocol. Whereas Beazley had failed to stand up to Howard’s refugee-bashing, Rudd promised to close the Nauru detention centre and adopt a more compassionate approach. Rudd also promised to withdraw Australian troops from Iraq, a very unpopular war that hundreds of thousands had marched against.

By far the biggest grievance with Howard was his WorkChoices legislation, which radically deregulated the labour market and used the law to severely restrict unions. The ACTU funded a massive advertising campaign against it and called national days of action that saw hundreds of thousands of workers strike and attend rallies. Rudd pledged to scrap WorkChoices, promising a “workplace where everybody gets a fair go”.

The other side of Rudd

While Rudd’s rhetoric was able to connect with a desire for change there was another side to his politics. He was no socialist about to shake up the status quo. He was absolutely committed to “responsible economic management” and saw himself as part of the “reforming centre” in the same tradition as the Hawke and Keating governments, but more willing to attack the unions.

Even before being elected he made business feel comfortable by establishing a business advisory group and putting Sir Rod Eddington, who had been a CEO and a director of numerous companies, at its head.

He was also socially conservative. He paraded his Christianity, opposed equal marriage, supported the continuation of Howard’s school chaplaincy program and criticised Bill Henson’s art as “revolting”.

Some Labor apparatchiks saw this as necessary to appeal to a supposedly socially conservative working class. Defeating Howard meant being “the son of Howard”, argued Rudd’s former press secretary Lachlan Harris.

But Labor’s landslide win was a huge opportunity. Social attitudes under Howard had moved to the left. When Howard took power, only 17 per cent preferred increased social spending to tax cuts. Nine years later it was 47 per cent. After Howard privatised Telstra, support for privatisation dropped from 30 per cent to just 9 per cent.

The Liberals were so comprehensively thrashed on WorkChoices that once defeated they dropped all opposition to scrapping the laws. Labor had an “overwhelming mandate” to tear up WorkChoices, said the future Liberal treasurer, Joe Hockey.

While Rudd won the election by connecting with people’s desire for change, this is not what they got. WorkChoices was scrapped but only to be replaced by the Fair Work Act, which many unionists dubbed “WorkChoices lite”. The restrictive laws unions are fighting today were almost all contained in Labor’s Fair Work Act.

Rudd also maintained Howard’s Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) which was used to intimidate and harass construction unions. Two unionists, Ark Tribe and Noel Washington, were threatened with jail sentences for failing to answer questions from the ABCC during Rudd’s tenure. Labor went from promising workers a “workplace where everybody gets a fair go” to promising the bosses a “strong cop on the beat” in the construction industry.

Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations was very moving and grabbed international headlines, but at the same time he maintained Howard’s racist and assimilationist NT Intervention and extended income management and the BasicsCard into new areas.

Rudd’s commitment to a more compassionate approach to refugees turned out to be hollow as soon as a few refugee boats arrived and the Liberals attacked from the right. Rudd froze the processing of asylum claims for Afghans and Sri Lankans and had some boats towed back to Indonesia.

All these issues massively increased the disillusionment among Labor supporters, but the straw that broke the camel’s back was Rudd’s retreat on climate change.

Rudd’s “solution” was always mild and designed to be as inoffensive to big business interests as possible. He supported a market-based emissions trading scheme which allowed industry to pass on the costs to consumers, with plenty of exemptions and compensation for trade-exposed industries.

When The Greens, rightly, refused to vote for it because it was so ineffective, Rudd walked away from doing anything and, according to Newspoll, lost over a million voters in two weeks.

Moving to the right

As Labor crashed in the polls and the Liberals attacked, Labor’s response was to move to the right. This just made matters worse as it extinguished any lasting hope for real change.

The rightward shift was most obvious on refugee policy. Labor went from closing the Nauru detention centre to reopening detention on Nauru and Manus Island and exiling refugees there permanently, all in the hope of “stopping the boats”.

As Labor slid in the polls the party moved to dump Rudd as leader.

But his replacement Julia Gillard was just as hollow. She marketed herself as a traditional Labor reformer. But her “reforms” were not social democratic but neo-liberal.

Her “education revolution” meant adopting the Gonski funding model and establishing the My School website and Naplan testing. The My School website created a marketplace in education as better-off parents shopped around for better performing schools, while Gonski funding ensured private schools continued to milk the public purse. These “reforms” have only worsened the already high levels of social segregation in our schools.

Gillard’s speech attacking Tony Abbott’s misogyny did a lot for her feminist credentials. But she was also responsible for cutting payments to single mothers, forcing them onto unemployment benefits and its regime of harassment and punishment.

It wasn’t long before the disappointment set in again. In desperation Rudd was brought back to the leadership in 2013 just before the election. But Labor was already doomed.

Will Albanese be different?

Anthony Albanese has already committed himself to “fiscal responsibility”, using the size of the government debt as an excuse for refusing to commit to raising JobSeeker, boosting funding to public schools or to a hospital system strained to the limit by the pandemic.

Some hope that Labor will push for more serious change now that it is elected. But the experience of the last Labor government shows the opposite. Kevin Rudd come to power on the back of a far clearer vote for change, yet Labor still failed to deliver.

Even when Rudd’s approval ratings soared as he symbolically undid the legacy of Howard’s rule, when the opportunity to expand spending arrived in the face of the Global Financial Crisis, or when The Greens held the balance of power in the Senate under Julia Gillard, Labor still refused to launch a more ambitious agenda for change.

At the end of the day, Albanese today and Labor historically are both committed to working within the framework of capitalism.

It will take a significant increase in struggle from below to force real change.

Rudd won the 2007 election on the back of massive union national stopwork rallies. But those rallies turned from “Your Rights At Work—Worth Fighting For”, into “Your Rights At Work—Worth Voting For”. After workers had voted Howard out, the union leaders demobilised the movement and let Rudd and Gillard trash the victory over the Liberals and the bosses.

The victory over Morrison can fuel workers’ confidence that change is possible. But we learned last time that to really tackle inequality and injustice we have to go beyond getting Labor elected. This means building the rallies, strikes and mass movements that hold the real power to win social change.