A Solidarity pamphlet, published March 2017

1. The neoliberal university

2. The university drops a bombshell

3. The Let SCA Stay campaign begins

4. The fightback gets under way

5. Management steps back, the campaign steps forward

6. Debates in the movement

7. The Dean resigns, the campaign revs up

8. The end game

9. SCA staff

10. Conclusion

The neoliberal university

There is a crisis of underfunding across the entire university system, with students bearing the brunt. In 1981, 89 per cent of university funding came from the federal government. By 2010 it was just 40.5 per cent. Over the same period the corporate tax rate dropped from 49 per cent to 30 per cent. This has meant that students have been forced to pay for a growing portion of tertiary education. Between 1997 and 2014, the government contribution per student fell from $12,346 to $10,600 while the student contribution increased from $5183 to $7600.

Universities have always been degree factories but as government funding has declined they are run more and more like businesses. University bosses, the Vice-Chancellors and Deans, resemble corporate managers “headhunted” with big salaries.

There are cuts across the board on Australian campuses. In 2016, the Australian National University cut programs from its language school and the University of Western Australia announced 300 job cuts. This year started with 400 staff at the University of NSW facing redundancy.

Disciplines like art that do not fit the needs of big business or the logic of profit-making are increasingly seen as expendable, a burden even. The effort to gut the Sydney College of the Arts (SCA) must be seen in this context of a decades-long process of the corporatisation of tertiary education in Australia. Managers like University of Sydney’s Vice-Chancellor, Michael Spence, are paid to push more students through lower quality education, while squeezing more and more out of an increasingly casualised workforce.

Art schools have shifted from being places where students spent 40 contact hours with teachers learning specialised skills to places where honours students might have one or two contact hours with teachers and be given partitions for studio space.

All this is symptomatic of the warped logic of capitalism. Working against this logic, the marches, strikes and occupations to save SCA were part of a fight to stop one rotten decision by management, but they were also part of a fight against a rotten system that puts profits before people. The SCA campaign became one of the most significant fronts nationally in the fight against the tide of neoliberalism over the past year.

Solidarity students were involved in the fight to save SCA from the outset; building the open organising meetings; pushing to extend the fight onto the main Sydney University campus; and arguing for the strikes and occupation at SCA itself.

We are sharing our experiences so that students everywhere can see that it is possible to fight back and sharing the strategy and tactics that made possible one of the longest student occupations in Australian university history.

The university drops a bombshell

The university drops a bombshell

On 21 June 2016, the University of Sydney ambushed its fine arts students and staff, announcing that it was dumping its Sydney College of the Arts just as students began their midyear break.

The move to “merge” SCA with the University of NSW’s College of Fine Arts, recently rebadged as UNSW Art & Design, was announced by email and in the pages of Murdoch’s The Australian.

Sydney University stopped taking enrolments into its Bachelor of Visual Arts. With SCA’s studio space, staff, and facilities under threat it was clear that this was not a merger but a closure. The justification given by the university was that it wanted to create an “arts centre for excellence” with UNSW—a fiction that was later exposed when the merger was abandoned but the SCA closure continued.

After the merger was scrapped the university wheeled out a new proposal to “move” SCA to Camperdown campus. The proposal included savage cuts in the course of the move. Staff covered by the two unions the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) and the Community and Public Sector Union (CPSU) were hit hard. Sixty per cent of staff were to face the sack and the specialised jewellery, glass and ceramics studios were to be shut down.

To justify this the university switched to arguing that the college was financially unsustainable, running at a deficit of $5 million a year, despite the fact that it enrolled almost 700 students (almost a third of them postgraduates, whose fees are particularly lucrative for the university). To put that figure into context, the university recorded $2 billion in revenue and an $89 million operating surplus in 2015—even after paying Vice-Chancellor Michael Spence’s $1.4 million salary.

The “deficit” was based on a “space tax” invented by the administration. According to Provost Stephen Garton, every faculty paid the space tax but because SCA, housed in Callan Park’s historic Kirkbride buildings in Rozelle, required proportionally more space it was deemed to be in deficit. Management claimed that the site was too expensive to maintain, or as the VC put it, “the Business School is paying for SCA”.

Nothing could make the university’s neoliberal priorities clearer. The Business School was moving into the $180 million Abercrombie precinct, where tables and chairs alone cost $4.2 million, an amount almost equivalent to SCA’s alleged deficit. The claim that the Kirkbride buildings were too expensive was in any case a lie. During the course of the campaign, it was revealed that in 1991, then NSW Premier Nick Greiner not only offered the University the complex for use by SCA under a 99-year lease, but put $6 million towards refurbishments. The government also committed to paying for maintenance. The university was required to contribute just $180,000 a year (indexed). The government also gave the university the CBD building that housed its law school to do with as it pleased.

The Let SCA Stay campaign begins

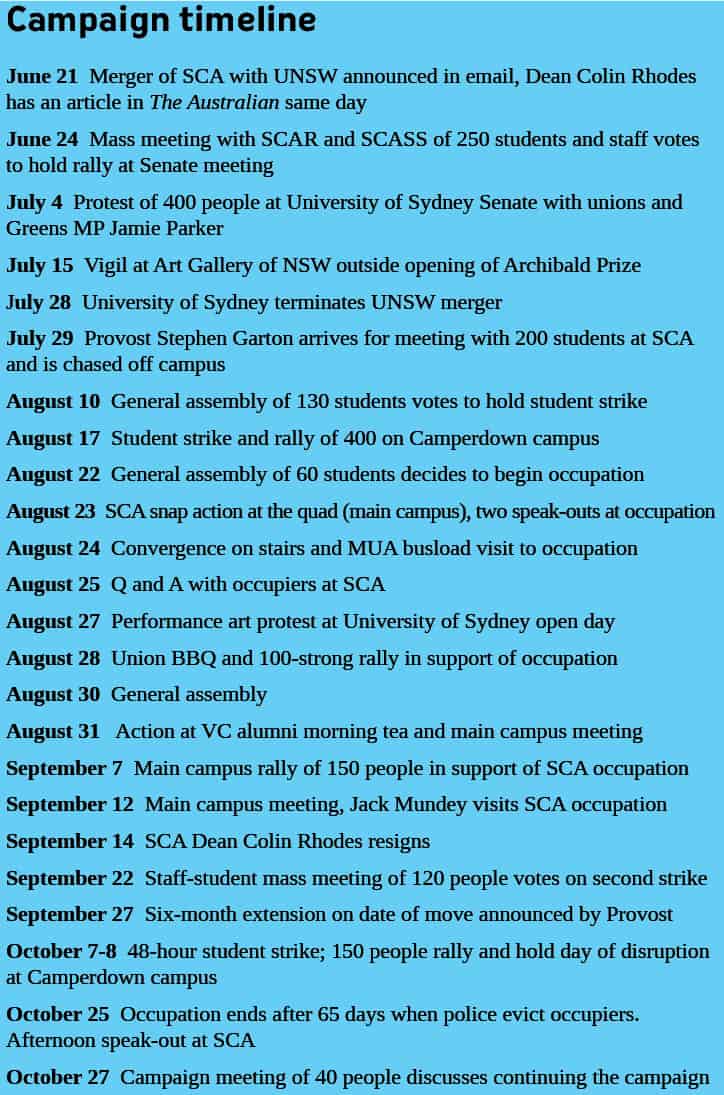

The original timeframe for the merger was very short and there was mass anger from the student body immediately. From the outset it was clear that there was potential for a mass campaign drawing in a large section of the campus at SCA. The campaign quickly developed in a militant direction—from the first mass meetings and rallies in June and July to a 65-day occupation of the Dean’s office by the second half of August.

The first campaign meeting attracted around 250 students and staff, as well as community supporters, where there was a huge amount of energy and determination to fight the closure. The Provost and Dean held a meeting to try and explain the closure, with 200 present, but students took it over, grilling them on stage about the closure and then escorted them off the campus—an excellent start to the campaign indeed.

The campaign quickly drew up its demands:

- Reinstate the Bachelor of Visual Arts

- Negotiations between the University of Sydney and UNSW to end immediately

- Preserve the studio space, staff, and specialised facilities at Rozelle, such as the largest printer in the southern hemisphere, kilns and glassblowing workshops

However, there was a great deal of confusion as to how to fight, largely due to a lack of experience organising campaigns amongst many SCA students and staff. Over the past decade or so there has been next to no political activity at SCA, which is isolated from the activism on the main campus in Camperdown, about five kilometres away across the CBD.

Earlier in the year, a group called SCA Resistance (SCAR) had been formed by a small number of mostly postgraduate students in anticipation of any changes or cuts that were likely to occur as part of a university-wide restructure. The group was willing to fight but was politically under-confident. The official SCA student society (SCASS) was far more conservative and determined to micro-manage the campaign and rely on lobbying the university administration.

More experienced activists argued against a top-down, committee-style campaign and in favour of regular, democratic organising meetings open to all who wanted to fight to save SCA. That argument won enthusiastic support from most students. It was also important to politically link the closure of the school with the logic of neoliberalism and the sterile cultural landscape that it produces, and to link it with the cuts happening across other parts of the university. This helped to make it clear to students that the fight to save the college had relevance far beyond the college itself and its current students. This was later vindicated by the national attention the campaign received.

From the first mass meeting of SCA students, it was argued openly that the campaign would need mass rallies, strikes and occupations to win. We could draw on the success of the 2012 campaign, when the University of Sydney put 340 jobs on the chopping block. Student activists organised leafleting and talked to students in lectures to reach out across the university. Mass rallies, student walk-outs and successful occupations of administration buildings were able to stop over half of the academic staff cuts.

The fightback gets under way

The first major action was voted for at the first campaign mass meeting—a mass rally outside a meeting of the University Senate, which is the top governing body of the university and could, in theory, overrule the Vice-Chancellor. The rally drew 400, which was impressive given it was on 4 July, before second semester had started. In a sign of management’s nervousness, the Senate meeting was surrounded by security fences and guards. Activists led the rally on a march into the new $180 million Business School, where students and representatives from the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) and The Greens spoke. This set a militant tone for the campaign that was to come.

The first major action was voted for at the first campaign mass meeting—a mass rally outside a meeting of the University Senate, which is the top governing body of the university and could, in theory, overrule the Vice-Chancellor. The rally drew 400, which was impressive given it was on 4 July, before second semester had started. In a sign of management’s nervousness, the Senate meeting was surrounded by security fences and guards. Activists led the rally on a march into the new $180 million Business School, where students and representatives from the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) and The Greens spoke. This set a militant tone for the campaign that was to come.

Some students insisted that displaying SCA’s talents and artistic productivity would be enough to save it. More experienced activists argued that it was useless to appeal to the conscience of management by convincing them of the importance of art in society—that the logic of neoliberal managerialism, which dictated their decisions, had nothing to do with whether or not something was culturally enriching.

Similarly, some of the more conservative activists went down the path of trying to prove that SCA could be saved by making it more commercially viable by advertising more widely among prospective students or seeking private partnerships or donors. These arguments that saw the fight to save SCA in isolation from the market-driven policies of the university management, were invariably linked to an “SCA identity politics” that argued only SCA students should be involved in campaign decision-making.

This tension was reflected in an action organised by an SCA student grouping running in parallel to the mass democratic campaign—a theatrical vigil at the opening of the Archibald Prize. The action drew a lot of positive media attention but relied on a strategy of appealing to the broader arts community for support, rather than attempting to build a grassroots campaign on campus. The theatrical organisers also neglected to give a speaking position to the NTEU, who they regarded at that point as peripheral to the campaign.

Management takes a step back, the campaign steps forward

The campaign scored its first success when the merger with UNSW was abandoned on 28 July and replaced with a plan to move SCA to the main University of Sydney campus from semester one 2017. The announcement was a partial concession but still meant three disciplines (jewellery, ceramics and glassmaking) and 25 of the 43 full-time equivalent staff positions would be cut.

The Vice-Chancellor announced that SCA would be merged into the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. The university also confirmed it would discontinue the Bachelor of Visual Arts from 2017, with a “re-imagined” equivalent to be reintroduced in 2018. Discontinuing the degree meant SCA would lose enrolments, justifying downsizing staff and restricting the courses offered.

SCA student Jemima Wilson summed up the mood of the campaign: “This is more motivation to keep fighting. The dissolution of the Heads of Agreement [for the merger] will not placate us and we will continue to fight to keep SCA at Callan Park.”

Activists circulated materials advocating a one-day student strike on 17 August and built a general assembly to vote on the proposal. The assembly was well attended (about 130 strong) and the vote for action unanimous.

On the day of the strike and rally there was a small speak-out at SCA, then a march through the school buildings to call out any students who weren’t striking and get them on the buses to the main Sydney University campus at Camperdown. There, about 400 people, including members of the two staff unions the NTEU and CPSU, held an extremely energetic march that took the message of protest to the Vice-Chancellor’s doorstep.

“A move to main campus is not suitable for the SCA,” Jemima Wilson told the rally. “There is no purpose-built, shiny new business school for SCA. We are not being relocated to something that retains what we love, and that’s why we have to fight.”

Activists were careful to prepare the way for further escalation at this strike/rally, organising for it to end by marching into a student administration building for a 20-minute disruption, where students made speeches calling for escalation. Having left-wing Greens leader Hall Greenland speak also helped set the tone for further militancy. There were references to previous student occupations in several of the speeches, which helped set the tone for the struggle to come.

Into occupation

To build the radicalism needed to win and send a clear message of defiance to the university, it was argued that the next step had to be an occupation of the SCA administration building. To do this many SCA activists had to be convinced of the need for a strategy of escalation, as opposed to continuing a many-pronged approach of constant lobbying, stunts and rallies.

The campaign had tried a mass petition. We had rallied, humiliated the Dean and Provost and we had held a one-day strike—we had to take things up a notch to show university management that we were serious. We propagated these arguments by circulating a leaflet at the 17 August rally/strike. It called for escalation and advertised a general assembly of SCA students the following Monday, 22 August, to decide on how we were going to escalate if management ignored the rally and strike.

It was decided in advance among the more radical students that we would try to use this meeting as cover to launch the occupation. This aimed to ensure maximum mass participation without giving the whole thing away in advance. Solidarity activists also compiled and circulated historical material about occupations at Australian universities and what they had won in the past to help inform the discussion among key SCA activists.

The decision to occupy was taken by vote in a general assembly of about 60 people. Only having a few days between the rally/strike and the assembly meant there was less time to build it, but it also meant the most radical students felt confidence bouncing out of the rally.

The occupation began on 22 August. While initially people thought it might go for a few days, it lasted for 65! During this time more than 100 people from SCA, the main campus and beyond (even a member of the construction workers’ union, the CFMEU, spent a night) maintained it on a rolling basis.

The occupiers controlled the top level of the administration building at SCA, which included the office of Dean Colin Rhodes. The student campaign called for his sacking.

The occupation became an epicentre of struggle, not just at the university but in Sydney, with regular events held inside and outside the building, including a barbeque with trade unionist, and leader of the 1970s green bans campaign, Jack Mundey. Friends of Callan Park and the Balmain community were a constant source of support for the occupation. It garnered rolling national media attention—almost all of it positive. Donations of food, money and supplies came from all corners and representatives from Aboriginal rights campaigns, the unions, activists from PNG and Myanmar all came to see or address the occupation, as did federal Labor MP Anthony Albanese. One very popular lecturer even held a couple of her classes inside the occupation.

“We wanted to make it clear to the university that if nothing changed or they didn’t meet our demands then we were going to escalate the campaign,” SCA student and occupier Suzy Faiz said.

“At a general meeting on Monday we had a vote on it and decided to occupy. When we walked in the whole meeting came in with us, about 65 or so people, and then when we barricaded the doors there were 20 of us left in there.

“It’s been quite organised, having three meetings a day, morning, midday, evening, discussing how we can get more students involved, how we can get outside support, and dealing with media”, Suzy said.

“When the occupation began I was on the phone all afternoon talking to newspapers, bloggers and radio. We’ve had a lot of unions that have signed on to support us, artists such as Mike Parr speak at one of the 1pm support rallies, Friends of National Art School who are also facing their own struggle at the moment, as well as staff and students.

“Over the past few days about ten other students have come in, and on Wednesday we had a visit from the Maritime Union of Australia with another group of about 30 who stayed for about half an hour.” The Sydney branch of the MUA announced a $1000 donation to the occupation during the visit, and another $1000 for the occupiers to create a piece of art.

“The university has said that they support peaceful student protests but they will not change any of their plans. So we definitely will hold this out longer, and the campaign will escalate until we get a reasonable response from them”, Suzy said. “This is about showing the university that we’re serious about our demands that we want to stay at Callan Park. This occupation is just a first taste of how future occupations will go if they try and physically move us from that space.”

Tamara Voninski, a PhD student at SCA, told a support rally: “We have staff jobs to save and facilities like glass, ceramics and jewellery to keep within our studio-based art practices. Taking away 60 per cent of our staff, and the campus, and our facilities, and 2017 enrolments for the BVA (Bachelor of Visual Arts) is wrong.”

Socialist activists were able to use their connections built with the unions to gain the material and political support needed to sustain the occupation, without which it is doubtful it would have lasted so long. Unions NSW, the peak body for unions in the state, embraced the campaign. This also allowed activists to make important connections between the government’s attacks on unions and the university’s attacks on its students.

Support for the occupation flooded in, along with widespread media coverage. Students addressed MUA stopwork meetings and received visits from MUA and CFMEU members, as well as a delegation of UNSW art students. The CFMEU matched the MUA’s donation of $1000, with $200 more coming from the NTEU at UNSW. When the university cut off the internet the MUA bought everyone dongles.

The occupiers addressed Unions NSW two weeks running, resulting in a union support demonstration on a Sunday that drew just over 100 people. The head of Unions NSW, Mark Morey, Labor MP Anthony Albanese and NSW Greens MP David Shoebridge all spoke.

In reprisal, the university attempted to suspend the swipe card access of two occupiers who were postgraduate students, Cecilia Castro and Eila Vinwynn. This prevented them entering 24-hour studios and study spaces. But a day later management backed down.

The campaign pushed more and more people to publicly condemn the university. Even a former Arts Minister for the NSW Liberals, Peter Collins, attacked the university’s plan. Ben Quilty, a former SCA student and Archibald Prize winner, visited the student occupation, saying: “I’ve come to tell you all not to give up.” (Later in the campaign, however, Quilty sided with the university management.)

An activist committee was set up at the main campus of University of Sydney to build support for the campaign across the university more broadly. Student activists held an “Occupation consulate” on the main avenue of the Camperdown campus to build support and promote actions. At least ten classes as well as staff in the School of Literature, Arts and Media held photo actions to support the occupation.

“The consulate’s been getting lots of support and it goes to show that people are seeing it as a fight for SCA but also a fight for all students and all staff,” student activist Sophie said. SCA postgraduate student and occupier Cecilia Castro reported with pride: “We have broken the record of the longest student occupation at Sydney University—Political Economy was occupied in 1983 for 10 days.”

Debates in the movement

Many challenges arose both from and within the occupation. The occupation was a lot more controversial than many activists expected. The campaign initially organised daily support rallies at SCA but when we went to build them we found debate in every class we went to. Some people were very supportive of the occupation, but there were also rumours that people were disrespecting the property of staff, that there were no SCA students in the occupation, that we were getting drunk and vandalising the offices. The rumours were being spread on Facebook and in person and they were gaining an audience.

Other students didn’t even know the occupation was there! On the one hand we had people from Germany ordering us pizzas from Dominos, on the other hand some SCA students who had walked past the occupation asked us “What occupation?” when we went to their classes. This hit the morale of the occupiers. Some began to doubt whether we should have occupied.

In the first days these doubts fed into a siege mentality and a focus on the internal dynamics of the occupation itself. As debate raged outside the occupation about struggle, cuts and corporate education, inside the occupation, the maintenance and internal functioning (rules, “safe space policy”, etc) of the occupation were debated at length, at the expense of building the campaign on campus.

To combat this isolation, on the third day of the occupation (to the dismay of management!) we organised a “convergence on the stairs” and opened the door to let 30 or more supporters in, including a busload of MUA wharfies. On the fourth day the occupiers went out and did a successful Q&A with 30 or 40 students on the grass. So one prong of the fight against those spurious rumours was to bring more students into direct contact with the occupation and occupiers.

Another prong was to organise solidarity messages. Members of the Public Service Association of NSW and NTEU members in Sydney and Melbourne organised motions and messages of support, including photo petitions. Other activists held support actions in their community or in their university classes. This, along with daily actions outside the occupation, helped shift the mood among the occupiers and give the occupation an outward-looking orientation.

An “occupation bulletin” was also launched to take on the conservative arguments being circulated to undermine the occupation. It had photos of the occupiers, written responses to various controversies, media sound bites, and listed the demands—no job cuts, no staff cuts, no studio cuts, the Dean should resign and be replaced by a representative committee of staff. The bulletin also listed supportive organisations and explained how a well-advertised student meeting had decided to launch the occupation. This was circulated around SCA and online. Activists also started putting out nightly video messages from the occupation on Facebook.

All this helped establish the occupation, brought new people in and cemented support for it at SCA itself. By the second week the destructive rumours were completely marginalised. One of the students who had been spreading them came out in support of the occupation!

Overall the experience of the occupation was immensely transformative and radicalising for almost everyone involved. It gave space to have more in-depth political conversations and raised questions as to how the university should be run and who it belongs to—the Deans and the university management or the students.

And on a campus where students had often complained that there was a lack of community and support, it was a shining example of how struggle can bring people together and create a feeling of solidarity among people who had previously considered each other as isolated classmates.

The Dean resigns, the campaign revs up

Halfway through the occupation, another victory! On 14 September, SCA Dean Colin Rhodes resigned. This was a public humiliation for the University of Sydney bosses, who clearly would have preferred to have a reliable and consistent attack dog overseeing the cuts, and it proved that management were feeling the pressure. And then another victory, the university announced it had delayed the closure of the Callan Park campus until the middle of 2017, after a challenge by the NTEU to the redundancy process slowed them down.

“They’re not ignoring us like they’re saying,” SCA student Cecilia Castro said, “we’re putting pressure on them.” But the fight was far from over. New acting Dean Margaret Harris made it clear she accepted the plan to close Callan Park, claiming the cuts were “what has got to happen”. As Cecilia said: “She even said to us that she’s getting paid by Sydney Uni and she’s here to do a job.”

Following our strategy of escalation to maintain the momentum of the occupation and keep the pressure on the university, we put forward the proposal for a two-day strike nearing the end of semester, on 7 and 8 October. Most SCA activists were convinced of the need for a longer strike but were reluctant to put the arguments to other students ahead of the general assembly. The result was that while the strike was supported by a meeting of about 120, many students were still confused about the rationale for the longer strike.

Following our strategy of escalation to maintain the momentum of the occupation and keep the pressure on the university, we put forward the proposal for a two-day strike nearing the end of semester, on 7 and 8 October. Most SCA activists were convinced of the need for a longer strike but were reluctant to put the arguments to other students ahead of the general assembly. The result was that while the strike was supported by a meeting of about 120, many students were still confused about the rationale for the longer strike.

At the assembly an activist who had been involved in mass student strikes in South Africa spoke well in favour of the strike, drawing on some of her own experiences. Two staff also spoke in support of the strike and the occupation. Painting lecturer Mikala Dwyer said the student occupation had been a “powerful symbol” and that “without it we would not have reached so many ears”. Matthys Gerber, a senior lecturer in painting, told students: “Artists need their fortresses and palaces… We are first and foremost an art school—and this is what we are protecting.” In the end, the vote for the two-day strike was carried overwhelmingly with just two students voting against.

The strike definitely delivered on the promise of unprecedented disruption. At least two classes were cancelled and moved—life drawing on Friday and sculpture on Thursday. First-year print media and jewellery ran with half and slightly less than half attendance and the student society meeting was forced to move.

The disruption was such that the acting Dean Margaret Harris felt the need to email students to insist that classes were on. One staff member who was against the campaign could only get her class to run by physically shepherding her students through the picket. A smaller campaign meeting also decided that we should barricade all the gates into SCA. The chains came out and only the front door was left open. Anyone who wanted to cross the picket line had to go through a single door and access was also cut off for cars.

After the morning picket at SCA there were buses to Camperdown for a rally and “Day of Disruption”. About 150 students and supporters rallied on the main campus. The group marched around in red bandanas and glittered masks, lecture-bashing classes to invite people to join them. A gigantic banner was dropped from the Quadrangle building and piles of clay turned into a sculpture at the entrance. A tent city, complete with a DJ, was set up on the front lawns. “This is the second strike, the first was a walkout from classes, to show that the student body is in protest at this current situation with SCA. We’re here to say you’re disrupting our education,” student Tim Heiderich said. “As long as we keep pressure up and keep our profile up, more of the movement’s demands are being met.”

The end game

The campaign was already at breaking point even before the second strike. People were exhausted and the situation was extremely volatile. The intense debate and conflict that came with the strike was massively amplified as the core campaign group went over and over the concerns raised by some students. In hindsight, it was a mistake to assume that most people would know that a strike would involve pickets of some sort to enforce the decision, so this aspect of the day had not been adequately discussed.

The strike took place in the lead-up to major assignments, meaning the stakes were much higher than with the previous strike. In the days before 7 October a handful of people who had had virtually no involvement in the campaign became very vocal in their criticism of the strike decision. They claimed it was “unfair” on students who wanted to finish their work (never mind that they wouldn’t be able to finish their degrees because of the closure), and that the decision to strike was undemocratic, despite the assembly and vote having been widely advertised.

In the absence of open meetings during this time, these voices became amplified in online debates, and SCA activists took them to be representative of the wider student body. However, a number of other students defended the strike decision online, often with more confidence than the activists themselves, and socialist activists did a good job at exposing the conservatism and self-serving nature of these arguments, which were often dressed up as being a defence of democracy or even of disabled students’ right of access.

By this point many of the core activists were physically and mentally exhausted. Some SCA activists felt the need to apologise for the strike, rather than defending it as being absolutely necessary. In the face of the criticism of the strike, some students tried to switch back to holding artistic actions, which were seen as more acceptable. The occupation continued on with a skeleton number of people until 25 October. Early that morning, the real face of the management was exposed. An army of 15 police and 20 security guards battered down the building’s fire-door, breaking it clean in half.

Occupier Che Baines, one of those evicted, said: “They gave us no warning, they came in at 6.45 in the morning. Not only did they evict us from our peaceful occupation, they then went into the campus and started ripping down art, [starting with campaign posters and banners], even posters that had nothing to do with the campaign advertising gallery openings.” Students at the occupation were issued official university notices threatening them with expulsion if they participated in further occupations. Activists responded with a small but positive rally to mark the end of the occupation, but not the end of the campaign.

SCA staff

SCA staff were covered by the NTEU and CPSU, both of which were supportive of the student-led campaign. But they had no industrial strategy of their own. They spoke at, advertised and organised to build for the student rallies. However, when the occupation was launched the NTEU was virtually silent for the first couple of days. It was the MUA which initially approached Unions NSW about backing the occupation. Then the NTEU followed suit.

The NTEU’s main initiative was to take the University of Sydney to the Fair Work Commission, claiming the plan to move the SCA breached “change management” provisions in their enterprise agreement. This delayed management’s plans but did not derail them. There was no attempt to mobilise SCA staff themselves, let alone take industrial action. The level of combativeness was so low that most staff remained convinced that they could be disciplined under the university’s code of conduct for publicly criticising the university’s moves, despite strong intellectual freedom provisions in the enterprise agreement.

The staff who opposed the closure and wanted to fight were pulled towards the more radical student campaign. One staff member held a tute inside the occupation, others sent food and supplies, several moved their classes during the student strikes and a few spoke at rallies. Others gave us a secret thumbs-up when we passed them. The staff actions bolstered morale and indicated the potential for rank-and-file initiative from staff.

However, with no pre-existing union activity and a climate of fear prevailing, the barriers to staff taking independent action were much higher than among students. A couple of activists tested the waters, but even a modest attempt to initiate a staff sign-on statement opposing the move or a collective staff photo in support of the occupation ran aground.

The NTEU welcomed the concessions won by the student campaign, but in December 2016 released a log of claims that demanded only that SCA move on the best possible terms. Staff industrial action always had a key role to play in the fight to save SCA and could have strengthened the campaign immensely. Socialists made constant efforts to link the students’ fight with the power that the staff have to take industrial action and really affect the functioning of the university. But the only way staff can strike outside the Enterprise Bargaining period is to break the law. NTEU support across the university would have been necessary to do so, taking on the management to remind them who has the real power in the university.

Conclusion

The university’s desperate and thuggish tactics in breaking up the occupation testified to its effectiveness. Management had been put under intense pressure by the record-breaking 65-day occupation, part of a mass, militant campaign that organised student strikes of a kind not seen on any Australian campus in recent history. The campaign won a series of victories:

- No merger with UNSW, which would have eradicated SCA

- The preservation of all mediums—including jewellery, glass and ceramics

- A 50 per cent reduction in full-time academic job cuts from 15 to 7.5

- The resignation of Dean Colin Rhodes, the public face of the planned closure

- The move of SCA from Callan Park delayed by 12 months—meaning 12 more months to fight

SCA’s defiance inspired support everywhere, from the arts community and university students nationwide, all the way to the unions on construction sites, schools and at the ports. The campaign was a beacon of hope for everyone fighting for a world that puts people before profit.

The fight to save SCA is not over. Between March and April 2017, the university has initiated a “spill and fill” process to make existing staff re-apply for their jobs. The university has used this process to cut staff pay levels.

Kurt Iveson, the Sydney University NTEU president, says that the proposed new site in the Old Teachers College on the main campus is “inadequate and fraction of the size of the old campus.” SCA student Suzy Faiz says there are currently no facilities and very little room.

No art students will be taught on the main campus this year, but no new students were accepted to commence the Bachelor of Visual Arts course in 2017. So the future of the art school is unresolved, and faculty after faculty at the university will face staff cuts, course cuts and mergers as the university-wide restructure continues to be rolled out.

The capitalist system inevitably forces people into situations where radicalisation and a fightback become possible. The management proposal to destroy SCA exposed a complete indifference to art practice and the welfare of students and staff. This angered people en masse. But it takes organisation to respond effectively. There is debate every step of the way in any campaign or struggle.

At the start of the SCA campaign there were debates over whether there should even be democratic meetings and rallies to save SCA. There were debates for and against the student strikes and occupation. If we are not organised on the basis of a clear theory of change that can guide us at each turning point, those debates can be lost. Without political leadership the inspiring struggle at SCA could have easily become a top-down lobbying campaign that quickly fizzled.

As Marxists, Solidarity understood from the start that university management is the product of a tertiary education system that was corporatised in the 1980s, and that universities are run like businesses, with Vice-Chancellors functioning as the CEOs, to meet the needs of capitalism. In their view art and education are just commodities. On this basis, we understood that they would have to be fought and not just reasoned with.

It was this understanding that led us to argue for the right tactics very quickly—tactics that involved mass mobilisation and gave people confidence and prepared them to fight. We understood that the rules we defy during acts of civil disobedience are there to prevent us using our collective power—that the legal system concentrates power in the hands of the few so they can better exploit the many. This gave us confidence to argue for the occupation and connect with like-minded students, despite the sometimes conservative slanders such as being “outside agitators”.

But throughout this whole process we didn’t just have ideas. We had activists on campus who were able to be in the meetings and at the rallies to make the arguments and write the leaflets. We had activists off campus who were able to send solidarity and draw on their past experience and union connections. We had a magazine, and branch discussions that were able to draw all the experience, theory and activity together amid an often bewildering frenzy of activity. Our organisation was effective because it already existed before the fight broke out at SCA.

Our consistent work over the years in Sydney and elsewhere has meant we have built a constructive relationship with the unions. One Sydney MUA rank-and-file member, speaking to the occupiers inside, noted all the “familiar faces” in the room from the 2015 wharf strike at Hutchison.

In the bigger picture, we don’t get to choose the moments when massive struggles, and even revolution, can potentially break out. But we do get to decide whether we are prepared. We have a responsibility to build a revolutionary socialist organisation that can help build struggles here and now, and in the future against cuts to education and cuts to penalty rates; against racism, sexism, and war; and against One Nation, Trump and Turnbull. Socialists are committed to individual campaigns as part of the fight to create a socialist society that produces for need and not for profit.

Join Solidarity

Reformism is a dead end. Acting as a lone revolutionary is a dead end. Real hope lies in revolutionary politics and organisation. We’ve seen a glimpse of that hope at SCA. We saw people stand up, get organised and fight. Students and supporters of many political stripes all made immense contributions to the struggle. But that determination to fight for a better world is most potent when it is organised. Capitalism provides the fuel, we need to spread the sparks.

Together, we are stronger. We need to look at the lessons of history and apply them in practice. If you want to be part of the fight for a better world, and a socialist future, join us.

The university drops a bombshell

The university drops a bombshell