Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism

By Natasha Walter

Virago, $35

Living Dolls is a compelling must-read for all those interested in understanding sexism today. Through interviews and research, author Natasha Walter maps the rise of “raunch culture” and the sexual commodification of women, which has undermined the gains of the women’s rights movements of the 1970s.

This book stands out in comparison to other writings on sexism because of Walter’s dissection of the crude biological determinism underlying mainstream accounts of sexism.

Living Dolls not only reveals the sexism of contemporary society but also shows how sexist ideas are produced.

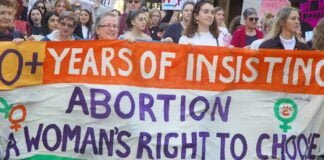

The women’s liberation movement won many crucial freedoms in the 1970s such as the right to contraception, abortion and acceptance of sex before marriage. However, as the movement declined sexual liberation was re-packaged and sold to women in the form of “raunch culture”.

This pervasive hyper-sexualised culture is seen in the increasing normalisation of the sex industry, with the rapid rise in popularity of strip clubs, prostitution and pornography in countries like the UK. It is also linked to the increasing sexual commodification of women in advertising, the media, movies, and society more broadly.

Many supporters of “raunch culture” argue that it represents liberation or empowerment for women, as it is their “choice”. Even many feminists argue this, reflecting the confused state of feminism today.

Walter was one such feminist who previously argued that the sexualisation of women was no longer a problem.

However, she now argues that the acceptance of “raunch culture” has reduced rather than increased women’s freedom. In co-opting the language of choice and empowerment it prevents many people from seeing just how limiting such so-called choices can be. Women have been increasingly forced into the narrow stereotype of a “living doll”.

“If this is the new sexual liberation”, she says, “it looks too uncannily like the old sexism to convince many of us that this is the freedom they have sought.”

Sex industry

The rapid growth of the sex industry has seen lap dancing and strip clubs become an increasingly common part of men’s social lives, from city workers to men’s bucks nights—especially in the US and the UK. It has become clear that some lap-dancing clubs are straight-forward routes to prostitution. Prostitution has also moved from the margins to the mainstream of our society.

This normalisation of women as sexual objects for sale is not only degrading and exploitative for the women involved, but impacts on how all women and men view women. Research shows the very presence of new clubs in communities appears to be associated with an increase in the rate of sexual violence.

The misogyny within the sex industry is self-evident, as men buy and judge women depending on their physical attributes.

One study carried out in England found that among men arrested for curb-crawling, more than three-quarters saw women who sell sex as dirty and inferior.

Violence and abuse of prostitutes is commonplace. One study found that two-thirds of prostitutes had been assaulted by clients, but fewer than a third of these crimes were reported to the police.

The hyper-exploitation and degrading nature of the sex industry is blatantly clear from the interviews conducted by Walter with women in the industry.

Cara Brett, a “glamour” model, revealed that the desperation of women often leads to exploitation. “So many girls do it for nothing”, she said. “A magazine, sits, do a shoot for us, and we won’t pay you, but you’ll get the publicity. They just do it. If you sell yourself at a low price, then you’re stuck. There are so many…”

Raunch culture also worsens women’s oppression across society. Pressures start at an early age. A survey carried out in 2006 found that one in four girls were considering plastic surgery by the age of sixteen. When interviewing a young women called Carly about the pressures of sex, her opinion was: “There aren’t any other options. There isn’t anyone speaking out against it. You’re just a sex object, then you’re a mother, and that’s it. There’s no alternative culture. There’s no voice saying that girls can be anything else or do anything else.”

The lack of freedom or “choice” for women is evident in the reality of women’s working lives and the still prevalent pressures for women to be primary caregivers.

The pay gap between men and women was higher in 2009 than in 1985. In Australia, averaged out women’s earnings are just 68 per cent of what men earn.

Women not only make up the bulk of those in poorly paid part-time or casual work but also still perform the majority of housework and caring of children.

For women who support raunch culture, gender equality for women is only defined through sexual allure. This is not a step towards women’s liberation but only increases pressure on women to conform to impossible standards. Women are now often expected to face the pressures of work, perform family caregiver roles and embrace the stereotype of attractiveness.

Biological determinism

Walter is critical of the resurgence in the idea that femininity is biologically rather than socially constructed. Biological determinism justifies the stereotypes forced onto women. Popular books such as Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus and The Essential Difference argue that having a male or female brain will fundamentally influence your occupation as an adult.

But she shows that research on male and female brains and hormones have failed to provide any consistent evidence of inherent character trait differences between men and women.

She points out that powerful voices in society like the media and educational institutions reinforce these stereotypes from a young age.

Boys are socialised to be interested in trucks and action figures and later learn maths and trades, while girls should be interested in princesses and dolls, then become nurses or teachers. This serves to justify sexism by making gender differences appear an inherent product of biology.

Walter’s strength is her ability to see the way in which the oppression of women is socially constructed.

However the final section on fighting sexism is disappointing.

Walter outlines ten possible initiatives such as campaigning against lap-dancing clubs, direct action against pornography or Reclaim the Night marches against sexual violence towards women. But all of these can easily fall into identifying men as the problem, rather than issues like childcare or wage equality for women workers that show how sexism harms men as well as women.

She also celebrates women’s self-help and consciousness raising groups as a way to deal with the rise in sexism. But wins for women’s rights require building a mass movement pressuring for change from below—and looking to build alliances between men and women. After all the gains of the 1970s were the product of mass protest movements for women’s liberation.

The commodification of sexual liberation is one example of capitalism oppressing ordinary people in the interests of the profits of a small minority.

Real women’s liberation cannot be built out of women’s only self-help groups or welfare groups but only a mass movement of women and men challenging the priorities of capitalism.

Feiyi Zhang