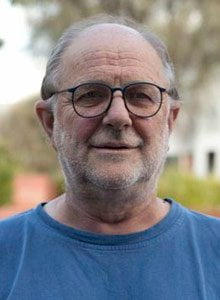

Michael Hyde was a student activist at Monash University during 1968. He was one of the anti-war activists charged by university authorities for collecting money to aid the Vietnamese resistance, the NLF. He spoke to Solidarity about the period.

My involvement at Monash started in 1967. I’d been living in America for a couple of years. I came back to a university that was already slowly rumbling.

The Labor Club carried out campaigns against restrictions in parking and that kind of thing, and of course the Vietnam War.

Anti-war sentiment was reasonably clear. The real change occurred in the second half of 1967 when we decided that if you were going to oppose the war you had to support the people who were resisting the American imperialists. That’s how we came to publicise and promote the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF). And that created a total shitstorm.

The Labor Club decided that we’d collect money for the NLF. That was stopped by the university administration. So a few of us collected in spite of that and were charged [under university rules].

It had a massive impact. The Labor Party defended the Defence Force Protection Act which the Liberals brought in, which was going to put us in jail for two years for supporting the Vietcong.

On every newspaper it made headlines and front pages.

Labor Party people in the anti-war movement went berserk and attacked us. They had people ringing us up saying we don’t want you carrying NLF flags at demonstrations.

In the wider community the response was often “I don’t agree with them, but I am against the war”. So taking a more left-wing position dragged people to the left.

The anti-war movement went to a much more militant phase. Whereas formerly demonstrations outside the US consulate were fairly calm and peaceful, in 1968 the 4 July demonstration erupted into a smoke bomb, rock throwing, horse charging frenzy. Over 60 people were arrested and some of us got our first taste of what it was like to be “interviewed” upstairs.

TV channels were doing documentaries on Monash University and the Monash Labor Club. There was another really active university [in Melbourne], La Trobe. A number of us were Maoists then and the same was true at La Trobe.

In 1968 I visited China during the Cultural Revolution. Then me and this other bloke both tried to enter Vietnam, but we were disallowed. So we got a flight to Phnom Penh [in Cambodia] and we flew over South Vietnam when the Tet offensive was occurring, which we only discovered a day later. I’d said to the flight steward, ‘what’s all that going on down there’ and he replied ‘Just forest fires I think’. He had no idea at all.

We were taking money to the NLF and had eight people to be signatories who were prepared to put their name on a receipt. When we got to the NLF embassy in Phnom Penh the consul was bringing out French liquor and celebrating. I translated his French to my mate and told him ‘I think there’s been a huge attack. They’ve attacked Saigon and attacked the US Consulate and it’s all over South Vietnam.’ So that was a moment in history.

Revolutionaries

It felt like everything was up for grabs. We’d also come in on the tail end of the civil rights movement in America. And a lot of us had been deeply affected by that.

There were a lot of changes in society as a whole, but I think that the beating heart of people becoming student revolutionaries was the Vietnam War. There were arguments at home, there were people thrown out of the family, there were people who lost their jobs.

My old man was a Uniting Church minister. He and my mother were left-wing Christians. There were many like them in the Protestant and Catholic churches.

And because there was action on the streets, and people handing out leaflets and organising it made people question almost everything, including the position of women in society.

The Vietnam War demanded something of people, made them look at the very essence of their society, when they found out people had lied to them about the war.

There were people involved in lots of different areas at lots of different levels. People who opposed the war at my father’s church in Wollongong held a vigil every Saturday morning. That basically led to my father being pushed out of that church.

A little known fact is that 12,000 young men refused to register for the draft.

We were spiriting people away, onto boats [at the docks]. Even my father told me years later that he’d ferried some draft resisters down the coast of NSW, taking people into safe houses.

There were lots of ways people would become involved, and the more they became involved the more left-wing they became. Because even when they did reasonable things their telephones were tapped, they were followed.

I was a pacifist, and a kind of a Christian, and one experience after another drove me further and further to the left, because I couldn’t see any calm moderate way of changing society. To this day that still rings true to me.

We felt as though we were part of a worldwide movement. There were huge demonstrations in London, in America and Paris.

We felt as though we were part and parcel of an upsurge and were delighted when we realised that when it came to the 1970s, per capita we had more people on the streets and actively involved than England or America.

Michael Hyde has recently published a memoir All along the watchtower. He also edited It is right to rebel, the classic account of the 1960s and 1970s Monash student struggles. More of his work is available at www.michaelhyde.com.au