As efforts to celebrate the role of Australian troops on the Western Front ramp up, Lachlan Marshall looks at how the horror of war gave rise to mutiny and revolution

As the centenary of the signing of the armistice approaches we can expect to see a flurry of nationalist myths about the heroism that Australian troops displayed on the Western Front.

According to Tony Abbott, “As a nation we have not given sufficient attention to our role on the Western Front where Australian forces made a disproportionate contribution to what proved to be, in the end, a great victory.”

One hundred years ago Australian troops joined Allied forces to defeat the last major German offensive, begun in March 1918.

To mark the occasion, the government is opening a new John Monash centre at the site of the battle of Villers-Bretonneux in France on Anzac Day, at a cost of $100 million.

But the war was a horrendous crime organised by Europe’s ruling classes in pursuit of empire and profit. The horror and senseless loss of life produced not just blind sacrifice but mutinies and rebellions among Allied troops beginning in 1917, and the eruption of revolution in Russia. In Germany it was revolution which finally put an end to the slaughter in 1918.

There is nothing in the mindless slaughter of the Western Front to celebrate. Millions died there in the most deadly and protracted battles of the war.

And there was nothing noble in the behaviour of Australian troops on the battlefield. Military historian Anthony Macdougall, although a believer in the troops’ “valour”, claims that by 1918, “the Diggers had gained a reputation for ruthlessness in battle, for shooting prisoners—something of which English soldiers were seldom guilty.”

The Battle of the Somme has become synonymous with senseless carnage and death. On the first day alone in July 1916, 21,392 British soldiers were killed. Around 23,000 Australians were killed in the space of a few days.

By the time fighting ended in November, 600,000 Allied soldiers and 650,000 Germans had died. For all this sacrifice, battle lines barely moved.

Another 300,000 died that year at Verdun, the longest battle of the war, again with neither side gaining any territory. The battle did succeed in wiping nine towns off the map.

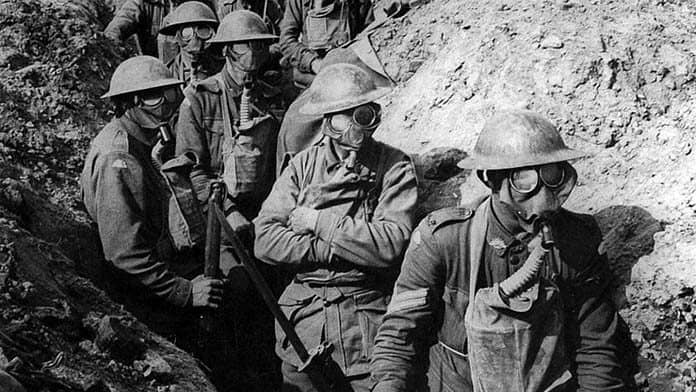

Verdun saw the first use of flame throwers, as well as poison gas by both sides.

One soldier recorded in his diary: “Humanity is mad. It must be mad to do what it is doing. What a massacre! What scenes of horror and carnage! I cannot find words to translate my impressions. Hell cannot be so terrible. Men are mad!”

The top brass thought nothing of condemning millions of people to death. In the planning of the Battle of Passchendaele General Haig allowed for 100,000 deaths a month, and Lord Milner, a member of the War Cabinet, thought that, “to get the enemy away from the Belgian coast was worth half a million men.”

It was impossible to expose soldiers to this level of trauma without provoking resistance. Sometimes it was individual, such as soldiers self-harming so they could be sent home. Throughout the war 600 French soldiers were executed for deliberately shooting themselves. Others fled to neutral Spain.

Eventually mass mutinies would explode.

Soviets on the Western Front

Russia was first to rise up in revolution on 23 February 1917, when women workers began protesting bread shortages. Soldiers sent to put down the rising joined the revolution instead and the Tsar abdicated on 2 March.

News of the Russian revolution was greeted with peace demonstrations in Britain, Germany and across Europe. The revolution helped inspire a wave of mutinies and revolts amongst soldiers on both sides of the conflict.

Class divisions were stark in all the armies. Troops knew that while they died in the mud the generals were safe and warm, eating turtle soup.

In early 1917 50,000 Italian troops mutinied. On the German side, a seamen wrote that “A deep gulf has arisen between the officers and the men. The men are filled with undying hatred for the officers and the war.”

The incompetence of the generals and their indifference to the mass slaughter they unleashed produced deep disgust.

Aisne offensive

In April 1917 French General Robert Nivelle planned a major attack designed to break the stalemate. But the battle plans fell into the hands of the Germans. French soldiers walked into a bloodbath. Refusing to admit any error Nivelle continued to send soldiers to their deaths.

For the French soldiers this was the final straw. On 29 April a battalion refused orders to return to the front. The mutiny was contained briefly after the ringleaders were arrested and shot. But by 9 May half of the French army were refusing to fight, with soldiers singing the Internationale and shouting “down with the war.”

The mutiny lasted two months. The presence of Russian troops instilled a spirit of revolution and soviets were formed by both French and Russian troops.

French soldiers drew up these demands: “We want peace… We’ve had enough of the war and we want the politicians to know it. When we go into the trenches we will plant a white flag on the parapet. The Germans will do the same and we will not fight until the peace is signed.”

The mutiny was eventually put down through a combination of repression and concessions: Nivelle was replaced with General Petain, who promised an end to the suicidal offensives which had led to massive loss of life, while 3500 soldiers were court martialled, 550 sentenced to death and 49 executed.

Etaples mutiny

Later in the year there was another major mutiny among NZ, British and Australian soldiers. On 9 September 1917 a New Zealander was arrested for overstaying his leave, prompting a crowd of 2000 to surround the police station that held their comrade. Five days of insubordination followed, with military police evacuated while soldiers held meetings and demonstrations.

General Asser, sent to Etaples to restore order, recalled, “Discipline ceased to exist. Reinforcements would not get into their teams and a great mob of about 10,000 broke out then and in subsequent evenings and marched into Paris Plage. The place seemed as if there was a big strike on, crowds loafing about and so on.”

Eventually the generals gathered enough troops from elsewhere to bring the mutiny to an end. Over 50 soldiers were court-martialled, three imprisoned for mutiny and one executed by firing squad.

But the British ruling class realised that they had to offer concessions. So in October soldiers in Flanders received a pay rise and the notorious training grounds known as “bull rings” were shut down.

German revolution

The war finally ended in November 1918, not simply through events on the battlefield, but when mutiny and revolution spread through Germany to the point where it could no longer fight.

In early 1918 there were mass strikes against the war in Vienna and Budapest within German ally Austria-Hungary. Workers’ councils were elected in Vienna. A strike by two million workers followed across Germany itself, beginning in Berlin.

The Bolshevik Party, after securing the support of a majority in the Russian soviets, seized power in October 1917 and withdrew Russia from the war. German workers’ delegates met in Berlin and demanded that the government accept the peace proposals of the Bolshevik government.

With the Russians no longer fighting, the German High Command shifted its focus to the Western Front, launching a number of offensives.

But many soldiers had simply had enough and were starting to see the sense in the revolutionaries’ slogan, “the main enemy is at home”. One officer told General Ludendorff that, “he thought he had Russian Bolsheviks under him, not German soldiers.”

The German army experienced mass desertions, described as “the hidden military strike.” Between mid-1917 and the armistice over two million German soldiers deserted.

Even though it was clear that the war was lost for Germany, the naval high command decided to launch a last desperate attack on the British. In late October 1918 sailors in Wilhelmshaven refused orders to embark on what was a suicide mission. The sailors were arrested but thousands of other sailors and port workers in Kiel joined demonstrations, sparking the German revolution.

By early November the military authorities were falling like dominoes as workers’ and soldiers’ councils took over across Germany.

On 9 November a general strike began in Berlin. Reliable units sent to put down the uprising in Berlin joined it instead, and the Kaiser was forced to flee to Holland.

The revolutionary Karl Liebknecht, who had just been released from prison, led a throng of workers and soldiers to the imperial palace where they declared “the socialist republic and the world revolution.” Two days later on 11 November the armistice was signed.

This year the Australian ruling class will commemorate the “sacrifice” “our” soldiers made in defeating Germany 100 years ago.

But the end of the war saw many of the rank-and-file soldiers and working people at home rise in revolt against the rulers responsible for the bloodshed and suffering on a scale never seen before in history. They recognised that the workers of other countries were not their enemies, but rather that “the main enemy is at home.”

It is this anti-war tradition of mutiny, protest and revolution that we should celebrate, not the war that condemned millions to slaughter.

The danger of imperialist conflict continues today, as the world powers feed the bloodbath in Syria, and Donald Trump issues threats to China and North Korea. Capitalism is as dangerous as ever. The revolutions that ended the First World War contained the hope of a socialist society based on human need, not profit.