Cooper Forsyth looks at the ideas of one of the US’s most uncompromising fighters against racism, and what they have to teach the Black Lives Matter movement today

The racism of US society is being laid bare by a huge rebellion against police brutality.

This is not the first time that a mass movement calling for justice for Black Americans has shaken the US to its core. One of the most heroic of these struggles was the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, which ended segregation and led to equal rights for Black people.

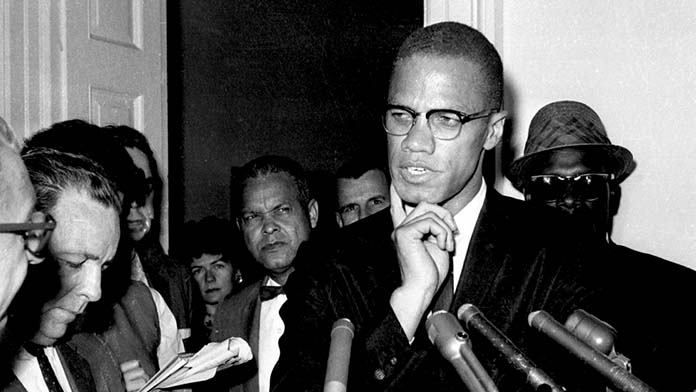

Malcolm X was one of the most uncompromising and principled fighters of this time. He grappled with many of the same questions that are still thrown up today: of violence or non-violence, the role of white people in Black struggle, and reform or revolution. For this reason his legacy remains important for anyone looking to fight racism today.

He was born Malcolm Little, in 1925 in Nebraska, in the US Midwest. At this time, Blacks in the Southern states of the US were living under Jim Crow laws, which enforced an apartheid system of segregation.

Racism was used to divide the working class in order to better exploit them, and to suppress labour struggles. It operated to the detriment of all workers, despite Black workers facing the most intense exploitation at work, as well as vicious racism.

In the North, things were not much better. While there was no Jim Crow, Blacks still lived apart from whites in overcrowded ghettos, suffering constant racism, lynchings, and massive exploitation as factory workers.

In the North racism was also used to suppress class struggle, such as during the strike waves of 1919, when Blacks were blamed by employers and the government for taking white jobs, with desperate Black workers from the South being used as scab labour.

From an early age Malcolm experienced racist violence first hand. When he was four, his family’s house was set on fire by a racist gang, and his father was killed by the Klu Klux Klan when he was six.

Nation of Islam

Malcolm was pushed into petty crime and served six years in prison from 1946.

It was here that he changed his name to Malcolm X, and joined the Nation of Islam.

The group combined Black Nationalist politics with ideas taken from Islam—calling for a separate nation of Black Muslims.

Its insistence on the greatness and potential of Black people was deeply attractive in the face of the humiliating position American society gave them. For this reason, it found a ready audience in the Northern ghettos, growing to 100,000 members in the 1960s.

However, while extremely militant against racism, and unafraid to call out the timidity of more moderate Black activists, the Nation of Islam was extremely sectarian and essentially abstained from political action.

They had a reputation for talking radical, but not actually turning up to act, let alone working with other groups.

They attacked the civil rights movement for working with white anti-racists. Instead of recognising the way racism is a product of capitalism, they called for more Black-owned businesses; hoping Black capitalism would be a solution to Black impoverishment.

Malcolm quickly became a key spokesperson for the Nation of Islam, agitating for their ideas around the country. He was a powerful orator and was deeply committed to the organisation that had helped him find clarity and purpose at the lowest point of his life.

Malcolm X gained notoriety in 1959 when he was interviewed for a TV documentary.

Rejecting moderate, legal challenges to racism he said, “When someone sticks a knife into my back nine inches and then pulls it out six inches they haven’t done me any favour. They should not have stabbed me in the first place.” The media immediately presented him as a “racist in reverse” and extremist fanatic.

This was a time of massive unrest in the Black population. The civil rights movement, along with other radical movements, was beginning to break the conservative atmosphere that had dominated politics. It opened up space for the emergence of a new left.

Martin Luther King’s strategy of non-violent resistance rested on the idea that Black people’s willingness to endure violence could demonstrate the moral superiority of the civil rights movement.

He aimed to push the Democratic Party leaders in the North to intervene against the racist Governors and police in the South. But in the face of the brutal, racist violence against the movement and Black people in general, many began to insist on the right to self-defence.

Malcolm X argued that Black people had every right to resist the violence that they faced. Even those formally committed to non-violence began to recognise its limitations. At a 1964 Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee meeting everyone was asked if they believed in non-violence. They all put up their hands. But when they were asked who had a gun they all put up their hands as well! The reality of the violence they faced meant it was common sense to be armed in response.

And in the North, where Black people already had formal legal equality, they were still ghettoised, terrorised by racists and police, kept out of solid jobs and in serious poverty. This showed that winning legal rights alone would not be enough to end racism, raising the question of how to achieve more radical change.

Rethinking

Malcolm gradually became disillusioned with the Nation of Islam’s sectarianism. He wrote in his autobiography that he privately felt that the group could be a, “greater force in the American Black man’s overall struggle—if we engaged in more action”.

In 1962 he attempted to launch a national campaign in response to the killing of seven Black Muslims by the Los Angeles Police.

Malcolm attempted to work with Blacks of other faiths, but was stopped by the Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad.

In 1964, Malcolm left the group. He abandoned its extreme sectarianism, but remained a Black Nationalist, believing that the solution to racism was for Blacks to organise separately from whites.

However, he also maintained an uncompromising hostility to the right-wing of the movement, which placed its hopes in the courts and the Democratic Party to bring change, as well as those who promoted non-violence as an unshakable principle.

His pilgrimage to Mecca the same year had a deep effect on Malcolm, who saw “blonde, blue eyed” Muslims, treating people of all races equally. Afterwards, as he travelled through Africa, he met Algerian independence leaders with white skin.

On his return to the US, he formed an organisation called the Organisation of Afro-American Unity, deeply inspired by anti-colonial struggles in Africa.

It argued for all Black Americans to unite regardless of religion and was on the radical wing of the civil rights movement. However it still essentially adopted “Black capitalism” as a solution.

The organisation was restricted to Black membership, as Malcolm argued that Blacks first needed to unite amongst themselves before they could unite with others.

However, Malcolm’s politics continued to develop, and he began to argue that some “sincere, well meaning” white people could play a role in the struggle against racism.

He criticised the Democrats and Republicans, not from simply a Black Nationalist standpoint, but as the representatives of a mostly white establishment, representing the interests of the ruling class.

He began to talk of racism as a problem of the entire system, famously saying, “you can’t have capitalism without racism”, and that the Black movement was not simply part of a racial conflict between Black and white, but a rebellion of the oppressed against the oppressor, and the exploited against the exploiters.

This is the closest he came to a class analysis which sees the system as to blame, and the uniting of all oppressed people as the only solution.

Tragically, Malcolm X was assassinated in February 1965, just before the Black movement and the radical struggles of the 1960s in the US reached their height.

But his ideas retain all their relevance today. Critics of the Black Lives Matter movement have condemned the rioting and property damage in response to George Floyd’s murder, failing to instead condemn the social conditions which lead to such outbursts of rage.

Malcolm X argued passionately against this perverse logic, which sees oppression as order and resistance as violence, arguing that Black people should fight racism by any means necessary.

Today’s Black Lives Matter movement first emerged under a Black President, Black Attorney General, and Black Secretary of Homeland Security, and is living proof of the failure of “Black capitalism” or of working through mainstream political institutions like the Democratic Party.

Channeling energy into getting Black people into positions of power has produced a growing Black middle class, but has achieved little for the largely working class Black population.

Today, there have been promising calls to defund and disarm the police. But again the Democrats, including racist Joe Biden, a man responsible for the Violent Crime Control and Enforcement Act, are attempting to co-opt the movement into campaigning to elect Biden as president in November. Malcolm would have rejected this dead end electoral road to change.

However, Malcolm X never quite grasped the possibility of uniting Black and white workers to both fight racism as well as the class oppression they have in common.

In the last month there have been a number of examples of workers taking action in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Transport workers have refused to carry arrested protesters and health workers have walked out to join protests. Ports on the West coast were shut down and on 20 July thousands took strike action in support of the movement.

Strike action forces workers to unite in solidarity across racial lines and has the power to shut down the economy to force real change. It can challenge the economic system which creates the poverty and degradation that Black people suffer the most.

And ultimately, it holds the hope of building a new world, where racism and oppression are obsolete.