Tom Orsag examines the life of Aboriginal activist Chicka Dixon, a wharfie, unionist, and bridge between the activists of the 1930s generation and the 1970s radicals

The Black Lives Matter movement has exposed the ongoing, systemic racism in both the US and Australia. The rich history of resistance to racism here has been shaped by numerous Indigenous activists.

Charles “Chicka” Dixon was born in May 1928, on Wallaga Lake Station, near Bermagui, on the NSW South Coast. He later lived at the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Reserve, near Jervis Bay, where traditional language and cultural practices remained strong despite constant attempts to suppress them.

The misnamed Aborigines Protection Board ran Aboriginal Reserves. The state appointed managers who controlled people’s work, movement to and from the reserve, and even how people’s houses were kept.

Children were taken from their families by police and “welfare” officers and put with white families or institutions. Notorious places like the Kinchela Boys Home subjected Aboriginal children to horrific abuse, including Chicka’s father Jimmy Dixon.

Jimmy Dixon worked as a wharfie, and Chicka followed in his father’s footsteps, getting a job on the docks at Port Kembla when he was just 14 years old.

Leading activist

In 1945, Chicka moved to Sydney and became a builders’ labourer. Later on, he gained work on the Sydney waterfront through connections with the Waterside Workers Federation (WWF), whose officials were from the Communist Party of Australia (CPA).

Chicka wrote of the CPA, “That’s where I learned the politics. The Communist Party… were masters at organising. And I learned a lot about other people’s struggles… I thought we were the only people in the world discriminated against. They taught me how to organise. We’d be talking about politics all the time. It was second nature”.

In 1946, on the day he turned 18, Chicka heard the legendary Aboriginal activist Jack Patten speak at the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs. Inspired by him, Chicka decided to devote himself to gaining justice for Aboriginal people. Patten was one of the organisers of the 1938 Day of Mourning in Sydney, along with William Cooper, Bill Ferguson, and Pearl Gibbs.

Chicka became a spokesperson for the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) after it was set up in February 1958.

Chicka was an important leader of FCAATSI’s decade-long campaign for a referendum on citizenship for Indigenous people. By the time the referendum was held in May 1967, with Chicka aged 39, he had become a national figure.

Prior to the referendum, Aboriginal people were not counted in the national census, denied many citizenship rights and remained under the control of different racist state-based “welfare” acts and special boards.

The referendum sought to break the control of these boards by shifting the power to legislate for Aboriginal people to the Commonwealth. The failure of the Commonwealth to use these powers to drive any real change spurred further radicalisation of the movement.

While FCAATSI was lobbying for the referendum, Black student leaders like Charles Perkins wanted to organise Sydney university students to take more direct action. In 1963-65, they toured northwestern NSW by bus on a Freedom Ride to disrupt the racist, segregationist practices of small country towns in swimming pools, cinemas, shops, clubs and pubs.

Chicka was drawn to the Freedom Rides. He wrote, “Looking back on the movement, from the time we went on the 1963 Freedom Rides to Moree and Walgett, things have changed tremendously. In those days you could only get two Blacks involved—me and Charlie Perkins—with a lot of white students on a bus.

“Today, when you ask Blacks to move on a certain issue, you can get a heap of them. But not then… Now we can muster 600 or more, so the pendulum has swung.”

The Aboriginal community in Sydney numbered about 2000 people before 1967. After the collapse of the Welfare Board regime on Aboriginal reserves, there was a mass migration from country areas. Within a year there were 35,000 Aboriginal people in Sydney. They wound up in the poorest suburbs of Sydney—Alexandria, Newtown and Redfern.

Chicka compared the lot of newly-arrived migrants from overseas to Aboriginal people, “Aboriginal migrants, who because of the lack of job opportunities, migrate from dirty government missions, river bank dwellings, reserves and fringe dwellings, to seek a decent way of life in the city. You may think the Aboriginal migrant differs from the overseas migrant, but I say my people have similar problems to overseas migrants.”

The NSW Police response to an increase in the Black population of the inner suburbs was as obvious as it was time-honoured in Australia—a campaign of intimidation and harassment.

This led Chicka and others to set up the first Aboriginal legal service in Redfern in 1970 to defend people against police brutality and incarceration. He and others also set up the first medical service for Aboriginal people, who faced chronic discrimination from health services.

Chicka was an important mentor for younger Aboriginal activists like Billy Craigie, Gary Foley and Isobel Coe and a key a link to earlier generations of Aboriginal leaders.

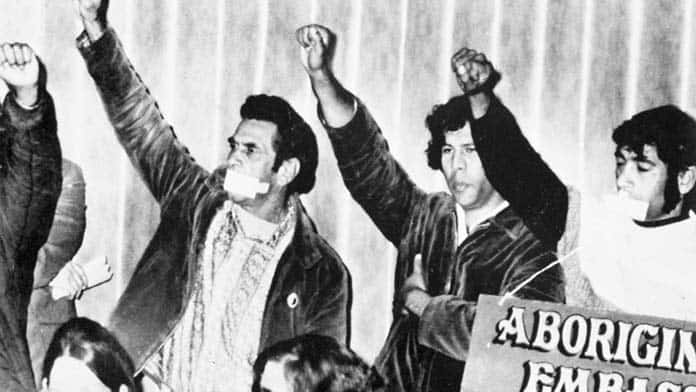

Under Chicka’s guidance, young activists established the Aboriginal Tent Embassy on Invasion Day 1972, after Liberal PM Billy McMahon publicly ruled out granting Aboriginal land rights.

Chicka had originally proposed they take over Fort Denison, in Sydney Harbour, and defend it in the style of the American Indigenous people in their 18-month takeover of the decommissioned Alcatraz prison in San Francisco Bay from 1969-71.

In July 1972, after the McMahon Liberal government ordered police to tear down the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, Chicka spoke at a rally of 400 Aboriginal people and over 1000 white supporters. He appealed to white Australia to vote the Liberals out of office in the election due in December saying, “If you are not part of the problem, then you must be part of the solution.”

Like every good militant unionist and socialist Chicka garnered himself an ASIO file. His file read, in part, he was a “popular, well-dressed and strongly anti-European dissident.” And as almost an afterthought, “He is an Aborigine.”

Union power

There is a rich tradition of Aboriginal activists organising strikes and other forms of union solidarity to build power behind the struggle against racism.

Chicka’s grand-daughter Nadeena Dixon has spoken about the long history of her family working in industrial jobs, living amongst the working class communities in Sydney and the Illawarra. While racism pervaded all levels of society, the experience of common hardship amongst the working class was an important foundation for anti-racist union solidarity:

“In the early days there was no OH&S protection… it was the man you were working beside every day that was the only one ensuring you went home safely to your family. And sometimes that man happened to have Black skin. This is how people came to see we have to stand together as a class, regardless of colour. This is how families and communities survived, by working together”.

Political and economic discrimination against Aboriginal people is intertwined in Australia because the state and bosses benefit from it.

In the generation of activists before Chicka, Pearl Gibbs organised strikes in the fruit and vegetable industry demanding equal wages with white workers, including a major 1933 strike by pea-pickers.

Bill Ferguson drew on his experience as an AWU organiser to build the Aborigines Progressive Association’s campaign for full citizenship in the 1930s, winning important support from the NSW Trades and Labour Council and many other unions and ALP branches.

A strike by WA Aboriginal pastoral workers against slave-like conditions in 1946 lasted three years. They won significant increases in cash wages despite police repression. Solidarity actions by unions, including extended bans by the WWF on the export of wool, were crucial for this victory.

Struggle by Aboriginal stock workers captured national headlines again in May 1966, when the Gurindji went on strike at Wattie Creek (Daguragu) in the NT, demanding payment of Award wages from the Vestey beef empire, rather than poor-quality rations. This struggle soon raised demands for the return of Daguragu to Gurindji control.

Chicka used his connections with the union movement to build an unprecedented level of support in the organised working class for the Black struggle.

When Vincent Lingiari and Mick Rangiari from the Gurindji came to Sydney in late 1971 to promote their struggle, Chicka played a central organising role in their speaking tour. His union, the WWF, donated $10,000.

As Harry Black, from MUA Veterans, said of Chicka, “He played a very significant role on the wharves continually putting forward the Aboriginal cause and working closely with the union to bring about support.”

Rhonda Dixon, Chicka’s daughter, played a key role leading the huge Black Lives Matter rallies in Sydney in June and July in 2020. Rhonda and her daughter Nadeena addressed MUA members at Port Botany on a smoko break in the lead up to the July rally.

Both women spoke about the huge gains made by Aboriginal people in the 1970s with the support of unions, and encouraged the workers to join today’s BLM demonstrations.

Rhonda told a story of Chicka and other Black workers being refused service at a pub in Sydney. In response, Chicka threatened to mobilise hundreds of unionists to protest and put black bans on the pub. Actions like this broke down many racist barriers.

When Chicka passed away in March 2010, aged 81, it was from a very working class disease—asbestosis, contracted from his time as a wharfie. Thousands attended a state funeral, where Aboriginal activist Gary Foley rallied the crowd to continue Chicka’s legacy of struggle and Chicka’s wharfie mates formed a guard of honour.

Dixon organised in an era where radical Black politics, socialism and a rise in working class struggle intersected to win many victories.

As a new generation of activists comes into the struggle through Black Lives Matter and the fight for climate justice, learning from Chicka’s incredible success will be crucial for the victories we urgently need today.