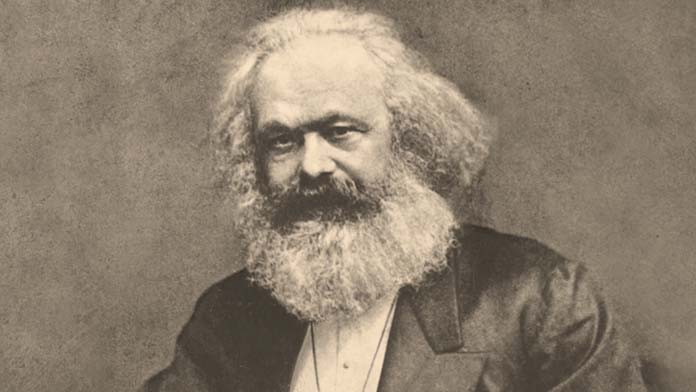

James Supple continues our series on Marxist classics by introducing Capital, Karl Marx’s masterwork examining the workings of the capitalist system

Recent years have seen renewed interest in Karl Marx’s Capital, the final product of his efforts to understand capitalism as an economic system.

Academic David Harvey’s books and videos, designed to guide newcomers through reading it, have been widely popular on the left.

Every time the world economy slides into recession Marx, as the capitalist system’s best known critic, receives another wave of interest. The near implosion of the global financial system in 2008 saw sales of Capital climb once again.

Capital is a monumental work that was the product of over three decades of effort, and was never fully completed. Marx was a perfectionist who found it hard to finish anything, continually writing and rewriting his drafts. Chronic health problems also slowed his writing.

Capital volume one, published just over 150 years ago in 1867, was the only part to appear in Marx’s lifetime, with the second and third volumes published by his collaborator Friedrich Engels from manuscripts Marx left at his death.

Capital is not an easy read. The first few chapters are famously difficult, as Marx begins by introducing a series of concepts that can seem quite abstract. But there are many useful introductions to Marxist economics that can provide a grounding in them first, as well as guides to Capital itself that can assist. The best of them is A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital by Joseph Choonara.

Marx argued that capitalism is based on commodification. It treats everything from food and housing to education, entertainment and even human labour as commodities that can be bought and sold.

So he begins Capital by examining the commodity. Any commodity has a dual nature, he says. It is an object that has some use to us by satisfying some need or desire, whether something vital like the basic food we need to survive, or a more frivolous desire like the latest model phone or smart watch. Marx calls this its “use value”.

But it is also a product that can be measured and exchanged for other products, with a certain “exchange value”.

This comparison of one commodity to another—one car might be equivalent to 10,000 loaves of bread, for instance—is necessary to exchange them on the market through buying and selling. Normally this is done using money to represent their value.

Marx sets out to uncover how the exchange value of different goods on the market is measured.

He argues that they represent the amount of labour required to produce them. As he puts it, all commodities represent “congealed quantities” of “human labour”.

This “labour theory of value” is fundamental to Marx’s analysis of capitalism. Most contemporary economists explain the exchange value of goods simply through supply and demand.

Marx accepted that this played a role in the short term fluctuation of prices. So the increased demand for cars during the pandemic has pushed up their price (as people try to avoid mixing with others on public transport). As life returns to normal and the supply of cars increases, prices will fall back again.

But no matter how many new cars are produced each year increased supply will not push their prices down to $10 each. Any company that tried to sell them that cheaply would quickly go out of business.

This is because the labour required to build and assemble all the parts that make up a car, which might take several days, have a much higher value.

So behind the temporary movement of prices up and down each commodity has an underlying value determined by the labour it takes to produce it.

How much labour power is embodied in any commodity is determined on a social basis, across the whole economy.

Someone who has never built a table before and uses only their backyard tools is going to take much longer to construct one than an experienced worker in an up to date factory churning out dozens or hundreds of them each day.

No one is going to pay more for the same kind of table, simply because it took an inexperienced worker three or four times as long to make it.

So the labour value of a commodity is determined not by the actual time it took to make each object, but the average time it takes to produce such a product, using the average level of skills and technology that are in use at that point in time. Marx calls this average measurement of the labour embodied in a product, abstract labour.

Profits and exploitation

The drive for profits is central to capitalism. It is a system where businesses set up production not because they think a product is necessary or important, but based on whether it is likely to turn a profit.

Marx wanted to establish where profits came from.

He writes that “the secret of profit making” is found in the special properties of human labour.

All commodities are ultimately the product of labour. Even the tools, factories and machines that workers use to create products were themselves put together by human labour. The raw materials like iron and steel that went into them had to be mined and processed.

The technology involved also required months or years of human labour time from scientists and engineers to develop.

But under capitalism, workers’ labour, like everything else, is itself a commodity. There is a “labour market” where workers sell their capacity to work to a company in exchange for a wage.

Marx notes that when, “a capitalist pays for a day’s labour-power… then the right to use that power for a day belongs to him”. Crucially, this means that a capitalist can get workers to create new commodities with a greater value than what they have paid the worker in wages.

The extra value extracted from workers beyond what they are paid Marx calls “surplus value”. This is the source of the capitalists’ profits. And it explains the extraordinary accumulation of wealth and commodities under capitalism.

It also shows that capitalism is fundamentally based on exploitation. For even well-paid workers will have part of the value they create taken from them to produce their bosses’ profits. The standard reason given for this is that the capitalist provided the tools, the factory or the workplace where the profits were created.

But how did they came to control this means of production in the first place?

The capitalists did not build the factories or workplaces themselves, they used other workers to do the job. The reason the capitalists own the factories is that they, or often their parents and grandparents, exploited earlier generations of workers to get rich.

Much of the first volume of Capital is dedicated to studying the methods that individual capitalists can use to increase the surplus value extracted from workers.

One method is simply forcing workers to work harder—such as through increasing the speed and intensity of work or lengthening the number of hours in the working day. This he called “absolute surplus value”.

Here Capital begins to show how this play out in the real world, with a famous chapter on the efforts by capitalists to increase the length of the working day during the early period of Britain’s industrial revolution.

Even today, bosses’ efforts to control the working day—from the McDonalds retail workers denied breaks to the monitoring of how long warehouse workers take for lunch—show capitalists’ continued efforts to extract the maximum labour from workers.

Accumulation

There is also constant pressure on capitalists to install new technology, equipment and production techniques and so to increase workers’ productivity.

Doing so allows them to produce a greater number of goods with the same amount of labour. Marx called this increasing “relative surplus value”.

One example is automation. In car manufacturing, robots and new machines have allowed the same number of workers to produce a far larger number of cars. So in the US, roughly the same number of cars were produced in 2015 as 15 years earlier, but with only 65 per cent of the workforce.

Companies that fail to introduce the latest technology face higher costs of production.

This means they will be undercut by rival companies able to sell their goods at lower prices.

This results in a constant pressure on companies to expand and accumulate profits. For without healthy profits they will not have the capital to invest in the up to date machines and technology needed to remain competitive.

Companies that fail to keep up are eventually driven out of business. This is one of the reasons for the dynamism and rapid economic growth under capitalism.

But it also means the system cannot survive without constantly squeezing more and more from workers. Exploitation and misery are structured into the system. Capitalism also produces environmental destruction and climate change, through capitalists’ constant need to reduce costs and maximise profits.

The three volumes of Capital explore many more elements of the system, including the impact of the circulation of commodities, credit and banking, Marx’s argument that the rate of profit would tend to decline over time and economic crisis.

But Marx was above all a revolutionary activist, dedicated to the overthrow of the system he studied. And the point of Capital, ultimately, is to show how this is possible.