In her book A Dream Foreclosed, Laura Gottesdiener calls the foreclosures and evictions of millions of American households since the start of the financial crisis “one of the longest and largest displacements in US history”. 99 Homes is an excellent film that tells a story about that displacement. The title is a deliberate reference to the Occupy movement’s slogan, “we are the 99 per cent”. As that suggests, the film is an unashamed critique of a system that rewards greed, opportunism and moral indifference.

It’s a classic dramatic thriller, but the bad guy isn’t a foreigner or a terrorist, he’s a rich white real estate developer with allies in the US government, business, and the police. His name is Rick Carver (played by Michael Shannon), and he swoops on foreclosed homes to evict the former home owners or tenants, scam government bailout schemes for extra money and then ‘flip’ the homes, making himself millions in the process.

In the first scene, he wears an immaculate white linen suit and does a business deal on the phone within metres of the dead body of one of his evictees, who has just shot himself in the head.

Carver’s real life equivalents are doing even bigger and nastier deals over the wreckage of people’s lives. The Blackstone Group, a private equity firm, has made billions flipping homes, and is now the largest owner of single-family rental homes in the US (in just one day, they bought 1,400 houses in Atlanta).

More than five million American families lost their homes to foreclosure between 2007 and 2014. And between 2005 and 2010, there were 929 suicides linked to evictions and foreclosures, according to a study in the American Journal of Public Health.

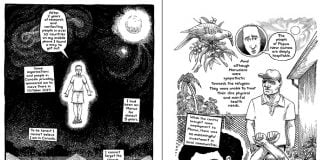

99 Homes is set in Orlando, Florida, where the rates of foreclosures and evictions are still the highest in the US. The eviction scenes are based on true stories from Orlando, of people who faced the violence of the banks, the bailiffs, the courts, the police, and the circling financial vultures.

Dennis Nash (played by Andrew Garfield) is a working class guy whose work building homes dries up during the housing crisis. After a sixty-second court hearing, he and his mother face eviction. They try to reason when Carver and the police show up. But there’s no reprieve for Nash, and they are out on the footpath with their life’s belongings in two minutes flat.

Nash suspects Carver’s workers have stolen his work tools. When he shows up to confront them, Carver seeks him out to offer him work in his corrupt scheme refitting the now empty houses with government money.

The deal-with-the-devil aspect of the film is so convincing and awful to watch because it’s just an extreme version of something working class people often experience—taking a job that compromises our values for the sake of putting a roof over our head and feeding our loved ones. We’re “free to work or starve” as Marx put it, and for the poorest workers among us, it’s often the dirty work we’re doing for a pittance: collecting debts; selling insurance; delivering the bad news in a customer service call centre; serving fast food or booze.

Nash’s first job is, literally, shoveling shit, in a foreclosed home where the tenants have blocked up the sewage pipes in a last act of defiance. But as the boss reels him in with the promise of getting his home back, Nash finds himself acting like the monster that ruined him, evicting devastated people from their homes.

We find out that Carver comes from a working class background, too. But, he tells Nash, “this country is rigged”, it’s “a nation for the winners, by the winners”. He’s become part of the one per cent through sheer ruthlessness. Will Nash follow his lead? You’ll have to watch it to find out.

The brutal eviction scenes in 99 Homes are still playing out every day in US cities. There’s plenty of talk of economic recovery, and foreclosures have slowed down, but only slightly. According to 24/7 Wall Street, the number of US homes in a state foreclosure in October 2015 was 463,000. Poor black single mothers are the most likely group to face eviction.

In one scene, Carver and his business associates forge a legal document in order to secure a foreclosure. But this isn’t just a story. In 2014, a leaked document from Wells Fargo, the country’s largest mortgage servicer, gave step-by-step instructions for lawyers to do exactly that.

In some of America’s poorest cities, like Detroit, the foreclosures come on top of massive manufacturing job losses. One in three homes in Detroit lies empty. In fact, the local government is receiving federal funds for “blight remediation”, meaning the demolition of empty homes. Yet there are 12,000 homeless in Detroit. Corruption is rife in the scheme: demolition contractors that donated to the Detroit Mayor’s campaign are overcharging the taxpayer by thousands of dollars per house. Truth is even more brutal than fiction.

Amy Thomas