Review: The Henson Case

By David Marr

Text Publishing, $24.95

WHEN, IN May this year, the right-wing forces of Miranda Devine and 2GB radio came together to declare offence taken to Bill Henson’s artwork, which features naked portraits of children and adolescents aged between12 and 18, the NSW Police were listening.

Police raided the Oxley9 Gallery in Sydney and seized artwork to investigate the possibility of charging the artist under the Crimes Act. ACT police followed suit and Henson faced the prospect of criminal charges in two jurisdictions.

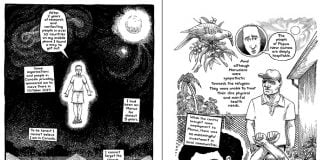

The old ‘family values’ argument that nakedness equals immorality took on a new dimension for right wing ideologues. Somehow Henson’s portraiture of adolescents (described by Henson as an effort to illuminate that flux period between childhood and adulthood, when sexual desires and life ambitions start rubbing up against societal pressures and constraints) was paedophilia and feeding a culture of such in society.

Most significantly, Kevin Rudd called the photos “revolting” not once but twice in a television interview after the seizure of the images, and declared them to have “no artistic merit at all”.

The sight of Kevin Rudd lining up with infamous censorship campaigners like Hetty Johnson was a bitter surprise for many who had believed they had voted for a socially progressive prime minister who could see the difference between nakedness in art and the exploitation of children in pornography.

It was a letter to Kevin Rudd from artists who at attended the creative stream of his 2020 summit that represented the first real defence of Henson and a solid, if mild, denunciation of Rudd’s fuelling of the hysteria. As the artists argued, Henson’s portraits were “more justly seen in a tradition of the nude in art that stretches back to the ancient Greeks, and which includes painters such as Caravaggio and Michelangelo”.

The Henson Case follows the case chronologically, and untwines the webs between reactionaries, the police force and parliament to show how the moral crisis spread. The writing is good and Marr is unmatchable at bringing alive the tensions and idiosyncrasies involved in people and stories, and he lays bare some of the contradictions in the positions of the censorship merchants.

He hits the nail on the head when he talks about the disappointment many felt about Rudd: “Those who had believed Rudd’s rise to power signalled some sort of shift in favour of liberty and free expression had to recognise that politics in Australia had changed again, only to remain the same.”

And so his explanation for Rudd’s conservative reaction is strikingly disappointing when it arrives. He seems to accept the idea it was born out of the prime minister’s personal morality.

But Rudd’s reaction to Henson had political purpose. Rudd wants to place himself firmly in the social conservative camp, and the Henson case was a golden opportunity to remind Australia he is the kind of prime minister who won’t stand for same-sex marriage rights or blaming anything but individuals for relationship breakdowns and poverty cycles.

It’s a convenient position when Rudd Labor have so far initiated no policy to increase essential social spending or restore the kind the welfare and education services we lost under Howard.

Not only that, but Marr misses the chance to dissect the ‘save the children’ argument deployed by Rudd and others. It bore a striking familiarity: not just to previous arguments to justify draconian censorship, but to his and Jenny Macklin’s more recent ones used to justify the intervention into Indigenous communities. In both cases, research and analysis about the real causes and instances of child abuse were ignored in favour of hysteria and a crackdown on civil liberties.

The government still neglects to fund any research into the incidence or prevalence of child abuse across Australia, and to provide funding for community-based schemes. Instead we have the removal of ‘artist’s merit’ as a recognised right under the Crimes Act in NSW to depict children who are victims of torture, cruelty, physical abuse or participating in sexual activity.

And as Solidarity goes to print the Australia Council will be revealing plans to demand all artists, galleries and publications sign up to protocols on the depiction of children or lose all federal arts funding. Artists portraying these realities are not the perpetrators, and nobody convicted on child pornography charges in NSW has ever attempted to use their ‘artistic merit’ as a defence.

The change is simply a cheap swipe at artists from a government angry at the embarrassing collapse of the case against Henson, and it sets a dangerous precedent for restricting the expression of dissent.

Marr misses the opportunity to bring these broader political issues alive in The Henson Case, but it’s nevertheless worth the time of those interested in them.

By Amy Thomas